Hearing Loss that Runs in Families

Does hearing loss run in families?

Yes, hearing loss can impact members of the same family. Let’s talk about some of the ways this can occur. One way hearing loss can affect families is through genetic inheritance. A person may inherit a mutated gene or genes that cause hearing loss1. In other cases, a person may have inherited undesirable genes.

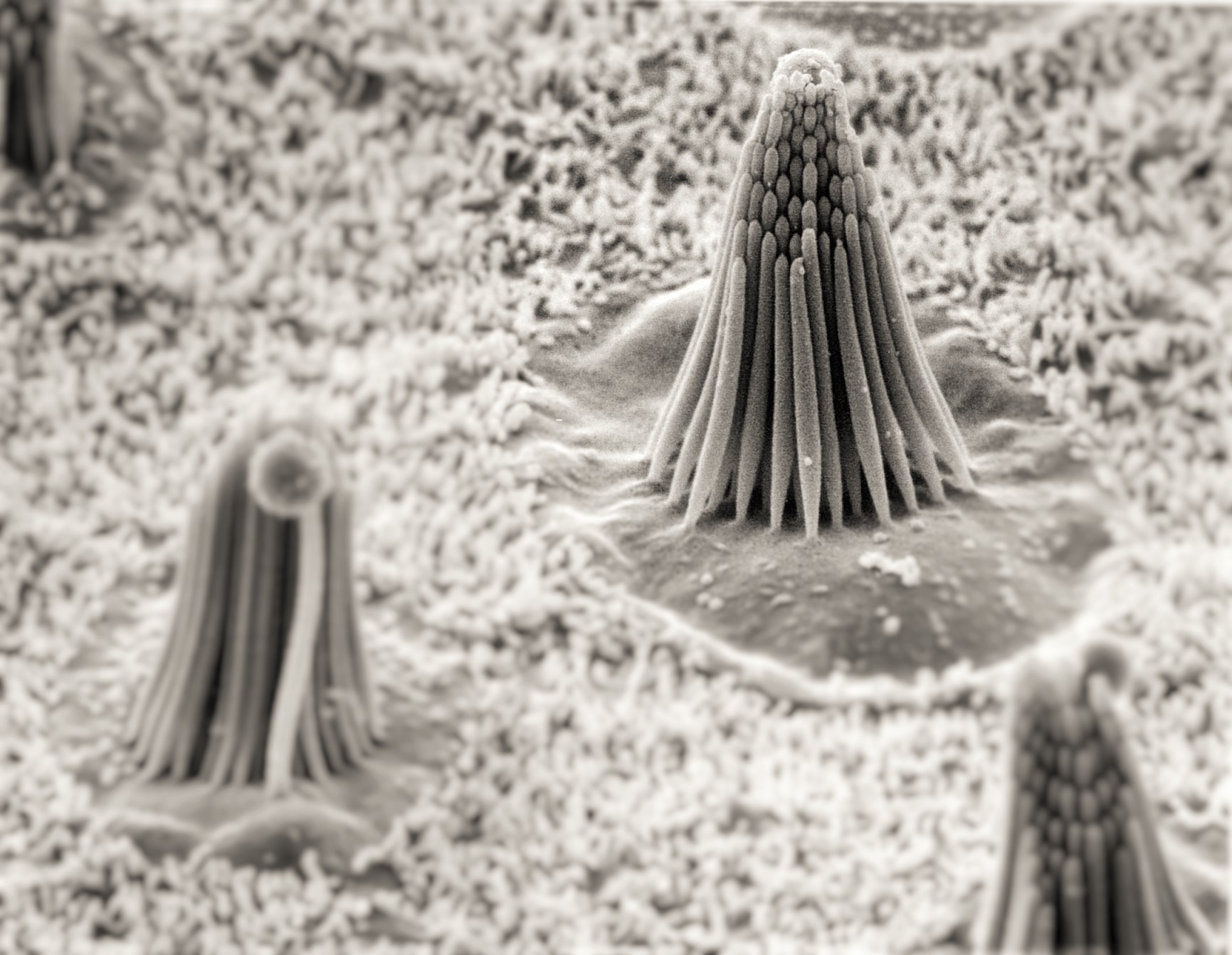

Hearing loss that is present at birth can be syndromic, meaning the individual will have other health issues present, such as problems with vision, balance, or even heart problems1. About 30% of inherited hearing loss is associated with a syndrome2. Examples of hearing loss associated with a syndrome are DiGeorge Syndrome, Treacher-Collins Syndrome, and Usher’s syndrome. The other 70% of the time, the hearing loss is not accompanied by other symptoms, and is called non-syndromic. An example of a non-syndromic type of hearing loss is GJB2 mutation. GJB2 is a gene that codes for a protein called connexin 26, found in the cells of the cochlea1.

In some cases, a person can inherit a gene mutation, but they do not experience hearing loss. This person is called a carrier1. A carrier of a gene mutation can pass it along to future offspring who might experience hearing loss. A child born with hearing loss of a genetic nature can have parents with normal hearing. Quite often parents are carriers of a genetic disorder and yet do not display that disorder themselves.

Hearing loss can also become apparent later in life, referred to as late-onset hearing loss. Late-onset hearing loss can be the result of noise exposure, medications, or health conditions that damage the auditory system. Several inherited genes have been identified as causes of hearing loss later in life3. For example, scientists have identified the DFNA10 gene, which causes progressive hearing loss later in adulthood3.

Finally, some bacterial and viral infections during pregnancy or shortly after birth can result in the presence of hearing loss at birth1. These infections are examples of non-genetic causes of hearing loss. For example, a child may have hearing loss present at birth if his or her mother had rubella during the early months of pregnancy.

Image by imagerymajestic, published on 13 January 2012

If I have a family member who has hearing loss, does this mean I will experience hearing loss too?

If you have a family member who has hearing loss, this does not necessarily mean you will experience it as well. There are several other factors associated with a higher likelihood of hearing loss, such as exposure to loud noise, smoking, high blood pressure, heart problems, and diabetes4. Another reason you may not experience hearing loss, even if a family member has it, is because not every family member inherits the gene mutation. Some gene mutations that result in hearing loss only affect males, while others impact females.

Certain types of hearing loss are not evident until later in life because they are “turned on” or expressed when a person comes into contact with environmental factors1.

If you have family members who experienced hearing loss later in life, you may have a genetic predisposition for hearing loss. Certain types of hearing loss are not evident until later in life because they are “turned on” or expressed when a person comes into contact with environmental factors1. For example, mitochondrial related hearing loss is genetically inherited, and can be triggered after a person takes an aminoglycocide (a type of antibiotic).

It is important to check your hearing to find out if you are also experiencing hearing loss. Talk to your doctor and audiologist if you are having trouble hearing, as they can help to determine what may be causing the loss, as well as the best course of treatment.

Learn More:

About the Test →

For Audiologists →

Read More Blog Posts →

References

1http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/hearingloss/genetics.html

4Agrawal Y, Platz EA, Niparko JK. Risk factors for hearing loss in US adults. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2002. Otology & Neurotology. 2009;30(2):139–145.

Bainbridge KE, Hoffman HJ, Cowie CC. Diabetes and hearing impairment in the United States: Audiometric evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999 to 2004. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:1–10.

Dalton DS, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein R, Klein BEK, Wiley TL. Association of NIDDM and hearing loss. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1540–1544.

Helzner EP, Cauley JA, Pratt SR, Wisniewski SR, Zmuda JM, Talbott EO, de Rekeneire N, Harris TB, Rubin SM, Simonsick EM, Tylavsky FA, Newman AB. Race and sex differences in age-related hearing loss: The health, aging, and body composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:2119–2127.

2Hilgert, N., Smith, R. J., & Van Camp, G. (2009). Function and expression pattern of nonsyndromic deafness genes. Current molecular medicine, 9(5), 546.

Nash, S. D., Cruickshanks, K. J., Klein, R., Klein, B. E., Nieto, F. J., Huang, G. H., … & Tweed, T. S. (2011). The prevalence of hearing impairment and associated risk factors: the Beaver Dam Offspring Study. Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery, 137(5), 432-439.

3O’Neill, M. E., Marietta, J., Nishimura, D., Wayne, S., Van Camp, G., Van Laer, L., … & Smith, R. J. (1996). A gene for autosomal dominant late-onset progressive non-syndromic hearing loss, DFNA10, maps to chromosome 6. Human molecular genetics, 5(6), 853-856.

Leave a Reply